It’s true that a week is a long time in politics. I wrote exactly a week ago about the upcoming referendum that would decide whether the U.K remained in the European Union, and I laid out just a taste of some of the mess of both campaigns – from the Remain campaign’s lost momentum and the repellent effect of David Cameron as the unintentional figurehead, to the Leave campaign’s underhand tactics and dog-whistle politics on immigration. It felt like an uncertain time, full of moments that seemed stranger than fiction.

I look back on the piece now and I can hardly believe how much more has changed and how much more is uncertain. As is often the way with these kind of huge events, society seems to only understand the significance of the movement in hindsight. Five days into the British exit from the EU, it’s beginning to look like one of most important political movements in my lifetime. And to the Leavers who say ‘get over it, move on’: this is step-change politics, and it isn’t going away any time soon.

When I wrote about my intention to vote ‘Remain’, I explained that I had come to this decision after reading up on the different campaigns and thinking about how problems within the EU – and yes, there are some problems – would be better tackled from within as a member state. My fear was that most people don’t have the time to think about their reasons for voting and what they want to see out of the referendum. My other fear was that despite how it felt at times this year like we were all sick to death of hearing about the upcoming vote, in another sense it also all felt a bit rushed. It didn’t coincide with a general or local election, and within both main parties some MPs were in favour of Leave and others in favour of Remain, without an actual coherent plan for either eventuality. Let’s be absolutely clear: there really was nothing planned for a Leave result. The outcome, like the preparation, is a complete mess.

In a shock result for both sides, 52% of voters (not the same thing as the population, nor as the electorate) voted to leave the EU and 48% voted to stay. I realised, not for the first time, that I live in an echo chamber where my friends and family are politically like-minded, but also that my Twitter and Facebook tend to foreground contacts who share my political beliefs (this explains the echo chamber effect on social media). Most media outlets had predicted a narrow victory for ‘Remain’ throughout polling day, and Nigel Farage conceded defeat to Remain late on Thursday night, only to backtrack at 4am on Friday morning with a euphoric speech declaring that we would be leaving the EU after all.

This speech, celebrating victory “without a single bullet being fired”, was either coldly calculating or wilfully ignorant of the human cost of dirty political campaigning. I suspect it was the former. You’d think the recent murder of Labour MP Jo Cox outside a library by a man reportedly shouting “Britain first!” would be the nadir of contemporary British politics, but Farage’s comment seemed almost like a dig at exactly that. His assertion that physical violence wasn’t necessary carried a chilling subtext of “this time”. As this video shows – in its uncut form to allay protests from UKIP that people share things out of context (hmm, sounds like pot calling kettle black), just a few weeks earlier Farage implied there would be violence on the street if ‘normal’ people weren’t listened to by politicians. As you can see, he didn’t exactly seem alarmed by the prospect.

David Cameron resigns (Lauren Hurley/PA via AP)

I felt an unnerving jolt of sympathy seeing David Cameron and his sombre-looking wife deliver his resignation on Friday morning, before remembering he (and we) would never be in this mess if he hadn’t selfishly pledged an EU referendum for his own re-election as Prime minister. He should never have gambled such an important issue for his own political gain whilst failing to think about people’s underlying dissatisfaction with the political order and their tendency to conflate immigration with economic partnership. Five days later and Cameron’s back in taunting smug mode, telling Corbyn to give up the fight for Labour leader, seemingly without irony.

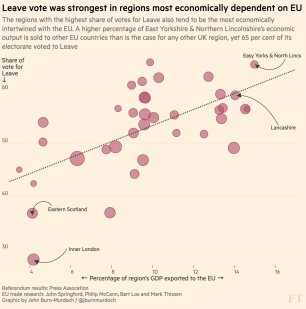

How (just) over half of the electorate want a future that looks away from, rather than towards, a European community is bonkers to me, but it’s a complex issue.We know that lots of it makes no sense: places like Cornwall, west Wales and post-industrial cities in the north-East were some of the strongest ‘Out’ vote yet also the areas with the biggest injection of EU funding, as this video shows. We are small, old country long past our global ‘heyday’ (if you can call a long history of rampant colonialism, rape and pillage a heyday) and we should be looking to Europe and the world as allies, not facing back inwards. Both Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson talked about the U.K’s very own “Independence Day”, seeming to forget that we never weren’t independent and also ignoring the fact that Scotland, having voted for Remain with a substantial majority, may now kickstart a second independence referendum, whilst Northern Island may reunify with Ireland. Little England seems a smaller place.

For the many who protest voted, or voted based on a particular issue but did not really think other people would do the same, and are surprised by the outcome, it’s like I said before: a vote’s a vote. There are more productive ways to show dissent, namely voting for an opposition party in elections: although I can see how that seems futile, watching Labour’s self-combustion in a crucial week when they could have been holding the Tories to account for the Brexit fiasco. And to be fair, many marginalised voters did demonstrate their dissatisfaction with the political elite by voting for UKIP last year – nearly 4 million of them in fact, obscured in part by the fact that these votes don’t convert proportionally to seats. Another way to engage politically – and I’m talking post as well as pre Brexit here, is joining a political party or your trade union, or writing to your elected representatives, which is easier than ever now with the They Work For You website. But all these methods rely on your knowledge of democratic rights as a British citizen, and this knowledge is not delivered by government or schools, and only rarely by other people.

People were angry, and voted to show that anger. The fault lies not with them (or at least not only them) but with the misinformation and prejudice of rightwing media and the misselling of what voting Leave in the referendum could achieve for those who felt like they had been ignored by British politics for too long, as Polly Toynbee points out so well (if you only read one thing today, make it that). As someone pointed out to the Financial Times, we live in a post-factual democracy. People don’t want to hear the reality, they want people who seem like them to be on their side and say what they want to hear.

What I like about our country is its cosmopolitanism and global worldview. Those people who voted leave in a bid to ‘get our country’ back are looking for something that never quite existed. What is it they want to get back? One answer is our control, rather than demands from unelected representatives. But EU representatives are nothing compared to the U.K’s unelected House of Lords, and besides, most laws are made in this country. Another answer is lower immigration, which doesn’t make sense when they’ve proven to provide net economic gain for the country and be more likely to work than Brits whilst less likely to use the state for benefits, healthcare or pensions, as this UCL study shows. Besides, as MEP Daniel Hannan admitted just hours after the result, exiting the EU wouldn’t really change inward migration anyway. People were lied to.

Re-negotiating our relationship to the EU will be incredibly complex, long-winded and expensive. I don’t think the phrase ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ should be used here, because there were things that needed fixing in the EU, but the point remains that we weren’t in a good position politically, socially or economically, to start a process we can’t easily finish. Thinking about all the serious issues facing the U.K before Brexit got in the way, from housing to the environment, from NHS privatisation to air pollution (whilst accepting that some are tied up in the same politics), and realising that these issues will go down the priority list whilst the government deal with a whole new crisis, is enough to make your head spin.

header credit: http://www.linkedin.com