Last week I wrote about the idea of digital detox as an escape from technology for an extended period of time. I’ve had lots of interesting feedback from readers, including links to this recent New York magazine article on our tech addiction, and this one about a summer camp for your midlife crisis(!), the latter sounding like privileged crap but also so intriguing I would quite possibly love it.

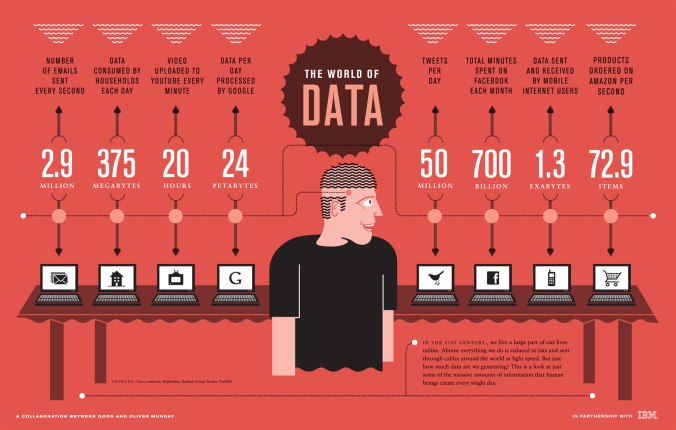

But there is another side to technology use, and that is the sheer size of data we are trying to process when we use the internet in everyday life. Think of it as data-day living (I’m so punny).

Data overload

It is clear that we are connected to technology in more ways than ever before: as well as desktop PCs and laptops, we now have excellent online capabilities via mobile phones, iPads, smartwatches, FitBits, public wifi, 4G, live updates, and more. I think few of us would take issue with the fact these connections allow us almost instant access to a huge array of information, from video to audio, science to literature, statistics to measurements. All this data ostensibly gives us ways to save time, speed things up, shop more easily, research information more easily, and access online content from all over the world. But the flip-side of this is that there is far too much data to process meaningfully at any one time. It is a data overload, and it often sucks up more time that it promised to save.

Don’t get me wrong, the internet is an amazing thing. I don’t regret emerging from a Wikipedia-hole an hour after googling ‘world’s tallest skyscrapers’ having learnt all sorts about non-skyscraper related stuff like New York’s population and the mixed fortunes of Dubai’s new carbon-neutral city. In this sense, the internet is not so far removed from a traditional physical encyclopaedia where one entry leads you another, and another, and another. In fact technology means those links are effortless and intuitive, as well as furnished with images, videos, and user-created content. But there is more information to sift than ever before, and this tests our capacity to filter the most important stuff and not get overwhelmed by the amount on offer.

How we consume data

This change in how we are invited to consume online content has happened in just a few years. The internet has allowed us in an everyday context to have the world at our fingertips, but our cognitive filters haven’t yet found a way of processing that richness. It’s dizzying stuff. Across the space of a mere decade or so, the average adult has had to change their information consumption style from in-depth focus on several sources, often vetted to prioritise the highest quality contributions, to grazing on multiple platforms all vying for your attention.

As for younger online users, the expediency of finding information online is certainly attractive compared to desk-based research. Imagine: you just type in your homework terms and rely on search engine algorithms to bring you the most relevant source first, at which point your own motivational powers dictate how much further you drill down. My experiences of teaching small-group work in secondary schools and after-school tutoring suggests that the answer is: not much. I’ve seen a tendency for students to uncritically ‘herd’ online resources or information into their written work, either failing to reference their sources appropriately, or using unreputable or user-generated sources as fact without critically evaluating those sources for who has written them and how objective they are. That said, schools are still better than many universities at teaching students how best to use the internet, not least because each course taught at university stands alone and relies on the student having taken courses before that adequately taught them the skills now needed.

Everyone’s a writer

Online information represents quantity but not necessarily quality. The contemporary explosion in user-created content – and my god, isn’t there a lot of it – means that quality is harder to control, and it raises the question of who even should be controlling it. Maybe one person’s idea of academic rigour is outdated, not to mention ineffectually slow, compared to another’s. Maybe content shouldn’t be controlled if we believe that the internet is a democratic space to which anyone can contribute.

I’ve written before about the diminishing future for editors in online content – after all, anyone can write a blog. I’m doing it right now, whilst surfing #brangelina memes (here you go). Who can even tell if it’s any good? Well, economically speaking, hit-counts provide a pretty good measure, and it is hit-counts for which we can blame ‘clickbait’ articles, which pull in advertising money based on increased online traffic from readers.

The question of who contributes to the internet is so interesting to think about because each answer has all sorts of repercussions. For example, as journalism skews more to free content, writers are less likely to get paid for submissions, meaning that the only people who contribute to the site will be those willing to contribute for free as young writers with a portfolio to gather, or those in a comfortable enough position not to need an income from their writing, or at least not all their writing.

Journalism has always been pretty cut-throat in that if you won’t write a piece for a limited fee, there’s plenty lining up behind you who happily will. Yet for any platform not using paywalls (The Times) or maintaining healthy income from advertising and sponsored content (Buzzfeed, who are going from strength to strength in their LGBT and #blacklivesmatter coverage), then the future relies – seems dependent, even – on unpaid writing.

Catching up

All this brings us back to evaluating the internet as both an amazing resource and something that has really changed modern life, in good ways and sometimes in difficult ways. Here’s where academia plays a useful part (I know right, never a guarantee is it). In-depth research on technology use is slowly catching up with the technology itself, and as it does so we will be able to learn more about how to make technology work better for us – and the extent to which that is differently figured for different people.