London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine serving 1920s Atonement vibes.

One of the interesting things in my post-doctoral research fellowship at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine has been researching the social science of public health.

A priority in the delivery of health services by the NHS for some years now has been patient and public involvement in healthcare. One example of this direction in healthcare that you might have heard about is the NHS initiative ‘No decision about me, without me’ (2012 – ongoing), which seeks to put the patient at the centre of the care that they receive, with the aim of better involving them in their own healthcare when ill.

In this free, open access article that me and my colleagues recently published for the Journal of Health Design, we look at this idea of patient/public involvement via ‘co-production’ – the idea that the public gets involved in shaping their care by working together with doctors and other healthcare staff to grant all parties the best possible results. For the patients, this is good health and a feeling of being included, and for the staff, this means good relationships with those they care for and healthy, happy outcomes.

It’s an interesting idea but not without its detractors (including for example: “Why should patients be considered ‘experts’ when that’s what doctors spend 6 years in medical school for?” “Why is the NHS so reliant on buzzwords like ‘co-production’?” “Is this kind of involvement vocabulary just another fad?”) but there is a lot that I like about the ongoing shift to think more laterally about public involvement in healthcare. As well as being a good idea in terms of hearing from less-heard voices in the healthcare system, who have historically been marginalised and as a result suffered from poorer health, the consensus from the bodies that make up the NHS and NIHR (National Institute for Health Research) is broadly that these co-production approaches make a lot of sense in the modern hospital system. As well as improving patient-clinician relationships, patients feel empowered in having a say in the care they receive, and some outcomes also point to cost efficiencies. This is, of course, vitally important in a political climate which has sadly seen the NHS increasingly positioned as the albatross around the government’s neck, no matter the lip service they pay it when they’re put on the spot. Plus ça change…

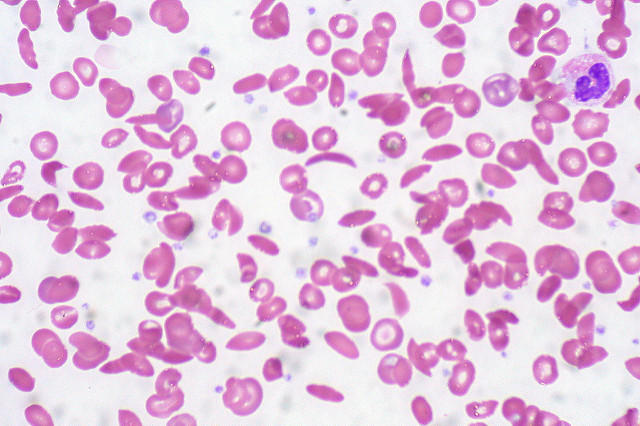

Either way, as a research field this kind of public involvement work is interesting for a whole range of audiences, and though the case study we use is our own ongoing research on young people with sickle cell disease (you can read more about ‘This Sickle Cell Life‘ here), the idea of ‘slow’ co-production, which emphasises quality, qualitative fieldwork that gets space to ‘breathe’, can be extrapolated to any number of different research activities that involve the public. And by involvement we’re talking here not just about the public as what has been seen traditionally as the passive research subject, something to be examined to aid in building our knowledge of social life; but in more meaningful terms as active collaborators in thinking about their care. Indeed, why not? Anything that can deepen people’s engagement with health and how they access and receive care has to be a good thing, right?

The article is free, open access and – rare indeed! – really quite short. Check it out if you fancy, here. Whilst I’m talking about public health, you might have seen that the NHS is turning 70! You can read about some of its amazing work over the past 7 decades here and here, plus check out the debate on Twitter here with the hashtag #NHS70LSHTM.