I’m very excited to publish a new article for Progress in Human Geography, co-authored with my friend and former PhD supervisor Dr Regan Koch. ‘Inviting the stranger in: Intimacy, digital technology and new geographies of encounter‘ has been two (2!) years in the making, with lots of coffee and post-work editing. After rewrites, rethinks and reviews, it’s finally out there in the world and it feels like our very own manifesto to the world (though I’m told delusions of grandeur are a sign of fatigue).

The Product

Regan and I had been talking for a year or two about how digital technologies are influencing the ways in which people meet each other, and what they meet each other for. When it comes to daily life for millions of people globally, meeting strangers online for intimate encounters has become the norm. Doing so offers experiences and rewards that are convenient, informative, sometimes meaningful, or which were simply less readily available previously. GPS-enabled dating apps (Tinder, Grindr, Happn) as well as sharing economy platforms (Uber, AirBnB, TaskRabbit) are built entirely on these kinds of stranger encounters.

Those of you who have read my work will know that it’s my ‘thing’ that digital technologies have progressed at such a dizzying speed that they have become incorporated into routine daily life faster than research can reflect on it, and that creates all sorts of questions that need to be explored and answered. I bang on about it all the time – what happens when you ‘meet’ someone on a dating app but when you convert online introduction to offline encounter they aren’t at all what you thought they’d be like? What kind of slippages happen in that shift? What is the etiquette for AirBnB – is your apartment owner a landlord, or a hotel receptionist, or a new friend who will give you the inside scoop on the city you’re visiting? Or are they all three, or another character altogether that you are having trouble interpreting?

We wondered if the idea of a ‘stranger’ is shifting from something unknown and potentially hazardous to something unknown and curious, or unknown but worth meeting, or even unknown but like-minded. Smartphone apps make meeting an unknown other a matter of choice not chance, and the processes often involve inviting a stranger into your actual home. What does this mean for how we relate to each other as a society? As we write:

As a society we have grown comfortable with stranger intimacies that would have seemed unusual in the recent past. App-based dating is the norm, the short-term letting of one’s home is common, and almost no one thinks twice about getting into a stranger’s car hailed via smartphone. Digital technology has helped to mitigate risks, but it has also changed the way people think and behave. The sociality of sex and dating has shifted such that many people are reluctant to approach someone in public for fear of rejection or embarrassment, yet are quite comfortable having intimate conversations online, discussing sexual preferences, sharing private photos and arranging at-home meetings.

Our point is not that we are inviting the stranger ‘in’ for the first time because of digital technology – that’s happened for centuries, and as Blunt & Sheringham (2019) and others have pointed out, the idea of home as private makes no sense anyway. Our argument is more that the decision-making process around how we encounter strangers has shifted with digital technologies to make stranger intimacies happen differently today, in ways which deserve critical consideration. And as Regan points out, it’s not just dating apps that are changing our geographies of encounter: ride-sharing apps, holiday rental apps, childcare, domestic help and DIY apps all bring the stranger ‘in’ using platforms that verify ‘matches’ through ratings, rankings, or public profiles. These products are incredibly useful for many people, and like dating apps, they can broker valuable social connections. They do however come with their own exclusionary politics – the privilege of smartphone ownership and access to 3G; the racialised, gendered and social hierarchies that are always at play in services that sell your ‘self’ (and yes, that includes dating apps); and limitations imposed by geography, economics and availability.

There are both opportunities and challenges for users of these innovative products, and rather than coming out as ‘for’ or ‘against’ them, we’re interested in thinking about how they influence daily life for a whole range of people. Our point is that digital technologies are kickstarting social encounters and ways of thinking about strangers and intimacy that deserve more study. As a conclusion to the article we lay out some ideas for how to go about this kind of research, and we consider which voices might be less heard when undertaking that kind of endeavour. One thing is for sure: apps aren’t going anywhere, and they are so central to many people’s lives (and livelihoods) that sustained social science research is long overdue.

The Process

For me, working together on this paper highlighted the opportunity to think big-picture. Together, we developed ideas that we really do think are important and that we hope signal a step-change in geographical and sociological thinking about how digital technology is incorporated into how humans interact in contemporary societies.

What the process also showed to me was the value in thoughtful, considered, long-term thinking. My enthusiasm to get words on the page and my tendency to sketch things out without looking at them from a range of different perspectives and viewpoints was usefully tempered by Regan’s slower and more methodical way of working. In a surprise to no-one, my random torrents of ideas, scatter-gunned on the page, really do benefit from another pair of eyes and another person’s thoughts. I have never written an article as closely with another person as this. My other co-authored pieces are certainly collaborative, but follow a more straightforward process of meeting with co-authors to discuss a topic and themes, circulating a growing text document, and meeting up again here and there in person (or now remotely) to continue our discussion. Different people take responsibility for different sections and we comment on each other’s ideas and arguments, but different papers have different ‘owners’. This is generally a good thing because it means that in a group effort, someone is corralling the process and making content and editorial choices.

But what was interesting about this piece was how it followed all of the above protocols but more intensely. This one document was more rewritten and revised, and more discussed, and more agonised over – line by line – than I’ve ever experienced, including my own PhD. The reading and researching was significantly slower, as was the writing process. We discussed theory a lot – far more than I would have chosen to, left to my own devices – in ways that made my brain melt but got me truly thinking analytically. It’s a time-consuming way of doing things and we could’ve filled the word limit three or four times over with the text content we ending up cutting, but the finished result hopefully speaks to a really concentrated product. I guess it’s like orange squash – Regan made me make sure that every line counted, every reference was thought-through and read (and re-read – Regan, if you’re reading this, know that I have never known a more thorough academic) and that every argument was ‘needed’ in an academic context where total written output grows exponentially by the day. I can’t speak for Regan, but I know that it was a productive process for me.

This kind of co-authorship takes time and that these things are corners that cannot be cut. It’s something I’ve thought a lot about with my LSHTM colleagues when it comes to co-production – something that we call ‘slow co-production‘ – but I guess I hadn’t applied it in my mind to the writing process itself, as someone who flings words on the page at a rate of knots. So here’s to more thoughtful writing.

And as for the paper? Now that it’s finished and out there in the world, we hope it takes on a life of its own.

That’s not all: in

That’s not all: in

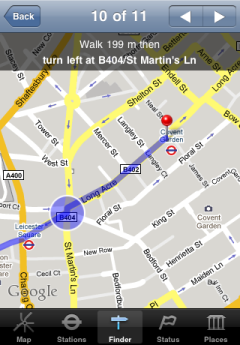

rch explores the ways in which dating apps might inform, or change, users’ perception of where they go, who they meet, and what they do in the city. This is especially interesting because these apps are skewed to urban populations, and the apps are the first of a generation to use GPS (global positioning systems;

rch explores the ways in which dating apps might inform, or change, users’ perception of where they go, who they meet, and what they do in the city. This is especially interesting because these apps are skewed to urban populations, and the apps are the first of a generation to use GPS (global positioning systems;  There has been a buzz growing around mobile-based dating apps for several years now, but we should not forget that the popularisation of location-enabled dating apps only really dates back to 2009, with the launch of Grindr. This was only narrowly predated by social network

There has been a buzz growing around mobile-based dating apps for several years now, but we should not forget that the popularisation of location-enabled dating apps only really dates back to 2009, with the launch of Grindr. This was only narrowly predated by social network